how do you serve an undercover cop?

and VCH workers publicly against decampment now count 100

How do you serve a lawsuit to the undercover RCMP officer who entrapped you?

The federal attorney general won’t take it. Nor will BC’s public safety minister.

John Nuttall and Amanda Korody sued the provincial and federal governments last summer, along with a slate of individuals. That includes Officer A, Officer C and Officer D.

The filing of the lawsuit was widely reported in late August, with the Globe and Mail saying the 22-page notice of civil claim “goes into great detail about the alleged tactics used by the RCMP to coerce the couple to plant bombs in downtown Victoria on Canada Day in 2013.”

Nuttall and Korody were arrested 10 years ago, so you’d be forgiven for needing a primer. If you haven’t already listened to it, and you’d like something in-depth, I highly recommends giving the CBC podcast series from last September Pressure Cooker a listen.

But for a quick rundown: Nuttall and Korody were a pair of recent converts to Islam. Nuttall was known to make violent and extremist comments, and law enforcement took notice. The two struggled with drug use and lived, for much of the time, in Nuttall’s grandmother’s basement and had little, if any, resources of their own.

But by Canada Day 2013, they’d been led by police to plant bombs near the BC legislature on Canada Day. Listening to the Pressure Cooker series, it’s easy to see how people would be concerned—Nuttall made comments about going to war against the West for Islam. But it’s just as easy to see how the police effectively manufactured the crime, and the court felt much the same.

While a jury convicted the couple in 2015, a BC Supreme Court judge tossed out the conviction the following year after an application by the defence for a stay of the proceedings due to entrapment and abuse of process. And in 2018, the BC Appeal Court, the highest in the province, upheld the decision, saying the police “eventually knew Mr. Nuttall and Ms. Korody had little to no ability to commit an act of terrorism.”

“They pushed and pushed and pushed the two defendants to come up with a workable plan. The police did everything necessary to facilitate the plan. I can find no fault with the trial judge’s conclusion that the police manufactured the crime that was committed and were the primary actors in its commission,” Justice Elizabeth Bennett wrote.

Officers A, C and D were three of four undercover officers in the case. The fourth, Officer B, is not named in the lawsuit. Nuttall and Korody’s lawyer, Nathan Muirhead, didn’t respond to an email with questions, including why Officer B wasn’t included.

As undercover officers, a publication ban has been placed on their identities (it goes as far as publishing their voices—the CBC’s podcast series, after an unsuccessful attempt to amend the publication ban, had to use actors to play recordings police had made of their conversations with Nuttall and Korody).

And that poses a challenge in the present case. This lawsuit was first filed in March 2021, and a year later, the couple applied to extend the notice of civil claim by six months.

And in August of last year, they filed their amended notice of civil claim, and the federal Department of Justice asked them to hold off serving the individual defendants until they could determine whether or not the government would be representing them.

In January of this year, the Crown defendants (that is, the Department of Justice and BC Public Safety Ministry) informed the court it would not be representing the individual defendants, and of the six named individual defendants, four have been served. What remains are two named individuals (unclear which ones), a John Doe and Officers A, C and D.

And that brings us to this week: Korody and Nuttall’s lawyers have been trying to figure out how to serve the undercover officers. As already mentioned, the BC and federal governments have refused to accept service on their behalf, and a proposal for the officers to voluntarily accept service through their lawyers hasn’t yielded any success.

As such, the couple’s legal counsel applied to serve interrogatories to the Crown defendants to get the names and addresses of the undercover officers. Interrogatories are essentially lists of questions, which have to be answered under oath, one party in a lawsuit can give to another as part of the discovery process prior to trial.

The Crown’s opposition to the interrogatories were four-fold: a) you can’t use interrogatories to obtain names of witnesses, b) naming them in interrogatories would violate the publication ban, c) the plaintiffs can “refresh their memory” or access the sealed court information if necessary and d) if they want the Crown to name the officers, they should apply to amend the publication ban.

Ultimately, the court agreed, citing the officers’ safety.

“Consideration first needs to be given to how to preserve the safety and security of Officers A, C and D and their families within this action. That may well involve extending the existing publication bans and sealing orders to include this action,” wrote court master John Bilawich.

As already mentioned, Muirhead didn’t respond to a request for comment, so it’s unclear what route the legal team will take.

Myles Gray inquest

I also just wanted to acknowledge that the coroner’s inquest into the Aug. 13, 2015 death of Myles Gray during an interaction with police is underway this week, through to May 1. Prosecutors declined to lay charges against the officers in 2020 after an investigation by the Independent Investigations Office of BC.

According to a summary by the BC Prosecution Service, two officers arrived to support Cst. Hardeep Sahota at 3:18pm. Ten minutes later, Gray was “unconscious, restrained with hand and leg restraints, and suffering obvious injuries.” Those injuries include bleeding in the brain and testicle, a possible dislocated jaw, and fractures in the eye socket, nose, throat cartilage and rib.

I’ve listened to a couple snippets, but it’s been a busy week for me. Unfortunately, those snippets didn’t include testimony by Gray’s sister, Melissa Gray, which kicked off the inquest.

But here’s a bit of what I have heard:

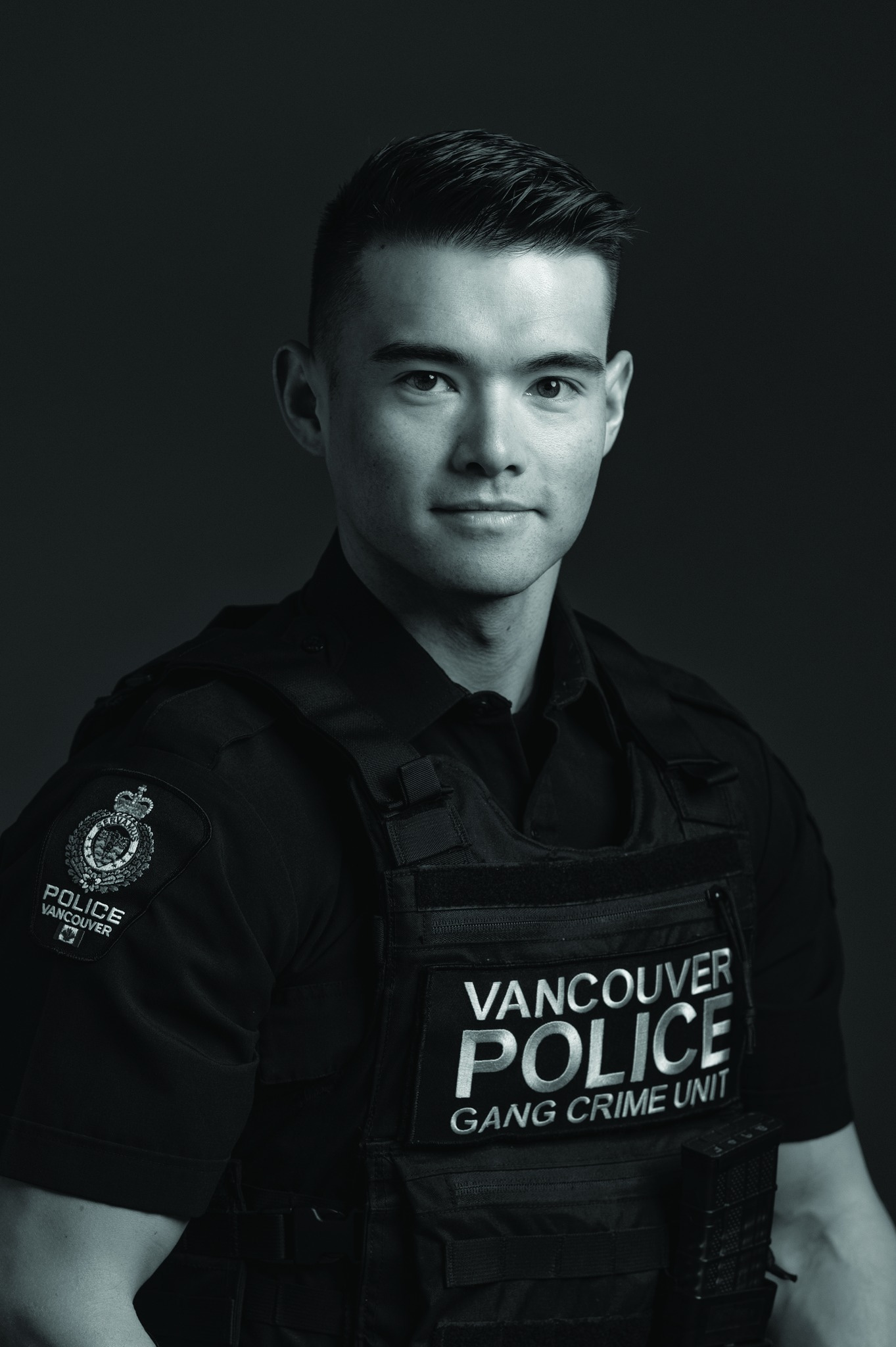

Yesterday morning, Cst. Josh Wong confirmed earlier CBC reporting to the jury that he was instructed by Vancouver Police Union officials not to take notes and that he heeded the advice as a young officer at the time.

Asked if this seemed normal to him, he told the jury the instruction seemed strange and out of the ordinary and that he didn’t know why they would do that.

And he told the jury that Myles Gray appeared to be extremely strong, and was able to throw him around, despite his being about 180 lbs. This, he later clarified, didn’t mean he was thrown like a ragdoll, but that he was easily handled by Gray.

I also heard testimony from a woman who’d called police after Gray grabbed her neighbour’s hose and sprayed her with it. In her testimony, which was done through a Farsi translator, she said Gray’s behaviour made her worried about her safety and about his.

An issue that will likely come up is drug use. According to the BCPS, Gray’s toxicology report came back positive for kratom, and a forensic pathologist was unable to say whether Gray’s death was a result of his injuries, each of which individually wouldn’t have killed him, or if it was for another reason—specifically the kratom or what is called “excited delirium.”

On the former point, it is worth noting that police have a long history of using drug use as an excuse for killing people or an alternative explanation for people’s deaths. (See: George Floyd) And on the latter, CBC had some important reporting earlier this week that coroners are starting to reject “excited delirium” as a cause of death. (Big shoutout to Bethany Lindsay for both this report and the other piece on the union’s directions on note taking.)

CBC also put out a piece on Melissa Gray’s testimony from Monday here, and CTV covered yesterday’s proceedings here.

One final note: The letter from Vancouver Coastal Health workers decrying the decampment in the Downtown Eastside has officially reached 100 signatories. The letter was first published a week ago with just shy of four dozen signatures. The link is to a Google Doc, but I understand the Georgia Straight publication will be updated sometime today with the latest additions.