Is crime out of control in Vancouver?

The data says: Not really

Last week, I published a big video essay on YouTube titled ‘Is Vancouver Dying?’ It was a response to Aaron Gunn’s “documentary” ‘Vancouver is Dying,’ and it was, I think, a very thorough debunking of Gunn’s arguments. I’ve had people reach out and say that it’s fine to have that big, long video essay that aggregates all of those big issues together, but they’d like it broken into something more digestible—which is a fair point, so here we are, looking specifically at the crime narratives.

****

The claim: “Crime is on the rise, violence is rampant, and residents don’t feel safe in their own communities—a trend that’s only been accelerating over the past few years. According to the Vancouver Police Department’s public safety indicator report, when compared to average crime rates between 2017 and 2019, 2022 has seen robberies up 21%, assaults against police officers are also up 21%, and violent assaults as a whole are up 36%.”

I want to note first that Gunn’s claims are based off of the VPD’s public safety indicators report for the first quarter of 2022, and I’ll be going off of the year-end report since it gives a more full picture. The second point I want to get out of the way here is that these are all police-reported crime statistics, and those can be unreliable, as they depend on consistency in how police report crimes they observe and how the public reports crimes they experience.

The public safety indicators report does show violent crime was up in 2022 in most cases, including assaults and robberies, when compared with the three-year average of 2017 to 2019. And this is, on the face of it, true.

But while Gunn’s video paints this in sensational colours, extrapolating really specific data into a broad proclamation that crime—especially violent crime—is skyrocketing, the data on this doesn’t really bear out once you zoom out a bit.

The public safety indicators report he relies on notes that, in the first quarter of 2022, assaults on police officers were up 21% from the three-year pre-pandemic average, along with the same percentage rise in robberies and a 30% increase in serious assaults.

Let’s address each of these three.

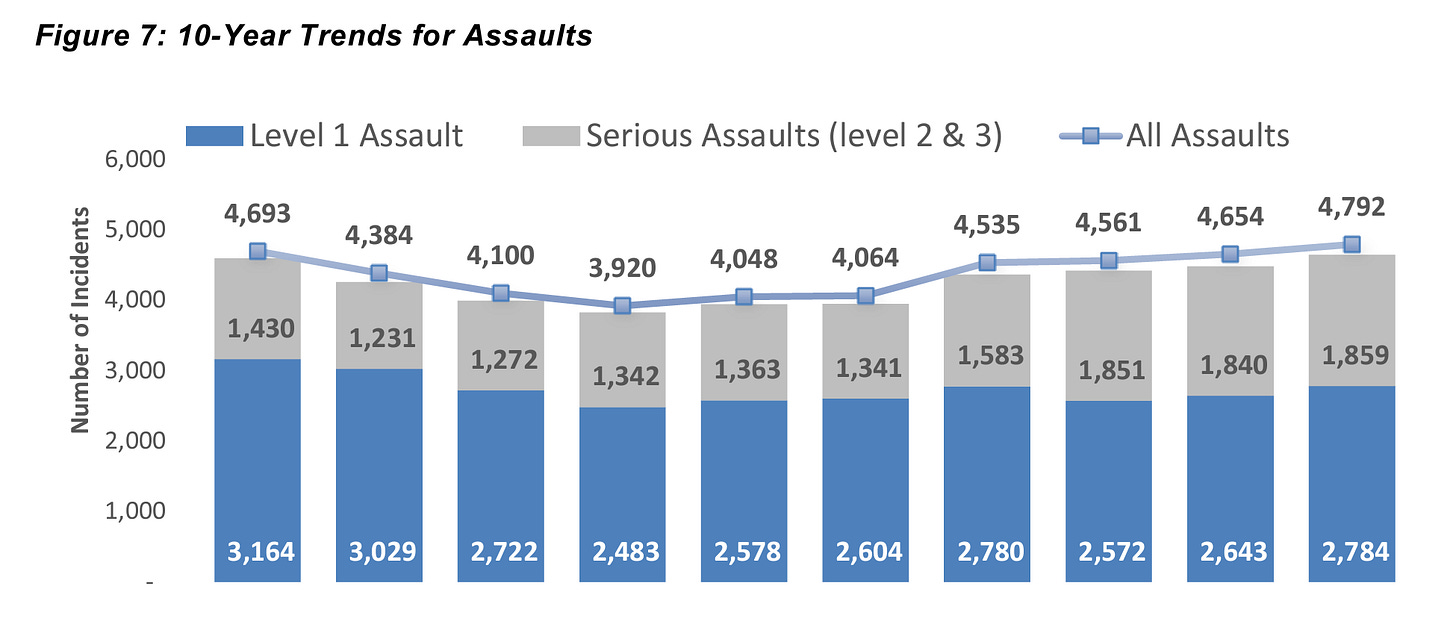

Violent assaults are up 30%: What he’s referring to are assault levels 2 and 3: assault with a weapon or causing bodily harm and aggravated assault.

And that, on the face of it, actually is true. And there’s certainly some room to be concerned about it, too. But first, some context.

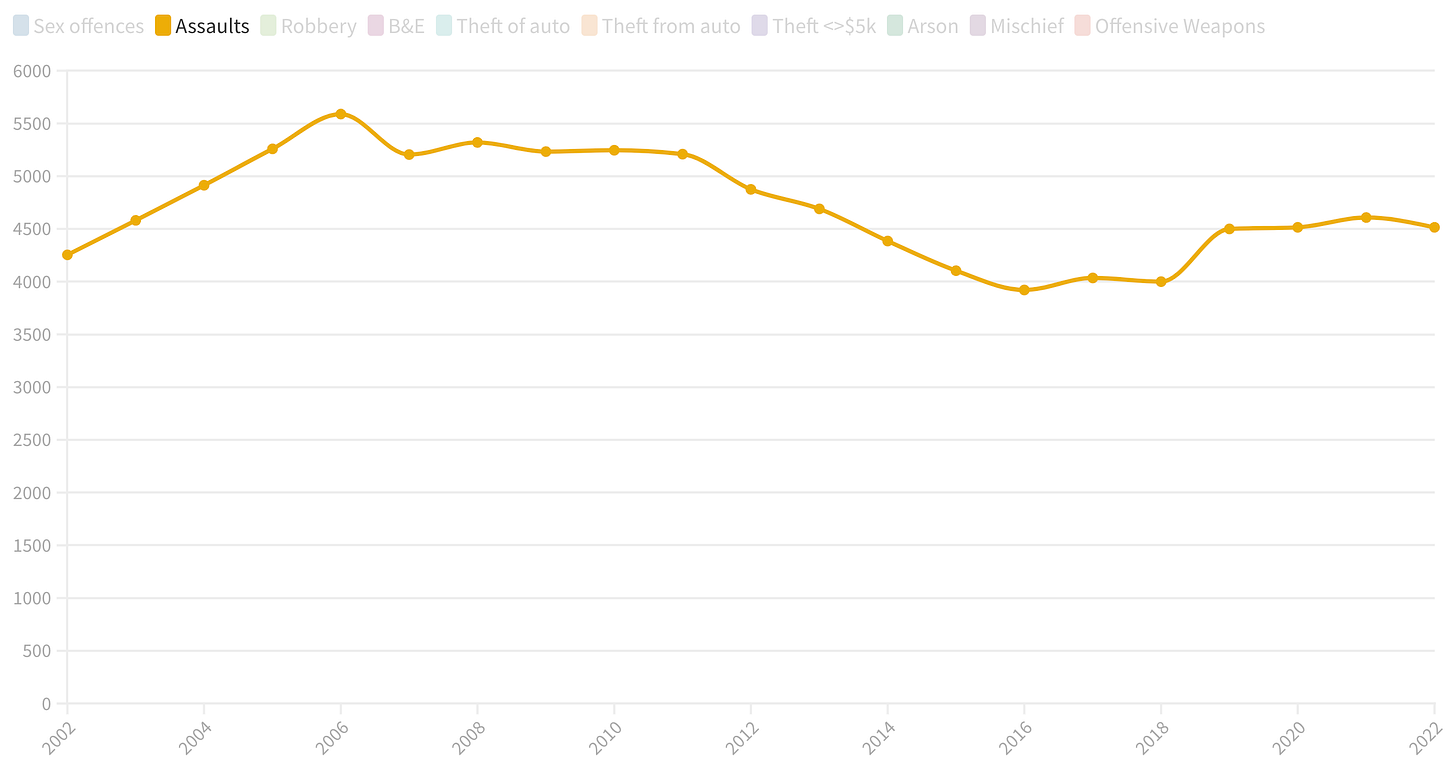

If you look at assault data, the peak of 5,200 to 5,500 incidents per year was very much in the late 2000s before dropping down to its lowest point of about 3,900 incidents in 2016. But since 2020, it has hovered at around 4,500 incidents.

However, one thing that’s a bit hidden in that data is the proportion of more serious assaults. In the last 10 years, there hasn’t been a substantial change in the number of level 1 assaults, but there has been a notable increase in serious assaults.

This is a trend particularly in the last three years, which does offer some reason for concern.

But if you want to claim that “Vancouver is dying” based on crime statistics, you’ll need a broader evidence-base than that. So let’s look at the other two claims.

Assault on a police officer is up 21%: Again, this is plainly true, but what the percentage point doesn’t tell you is that this is for a total of 152 incidents all year. It’s hard to make any case for this being some epidemic of violence.

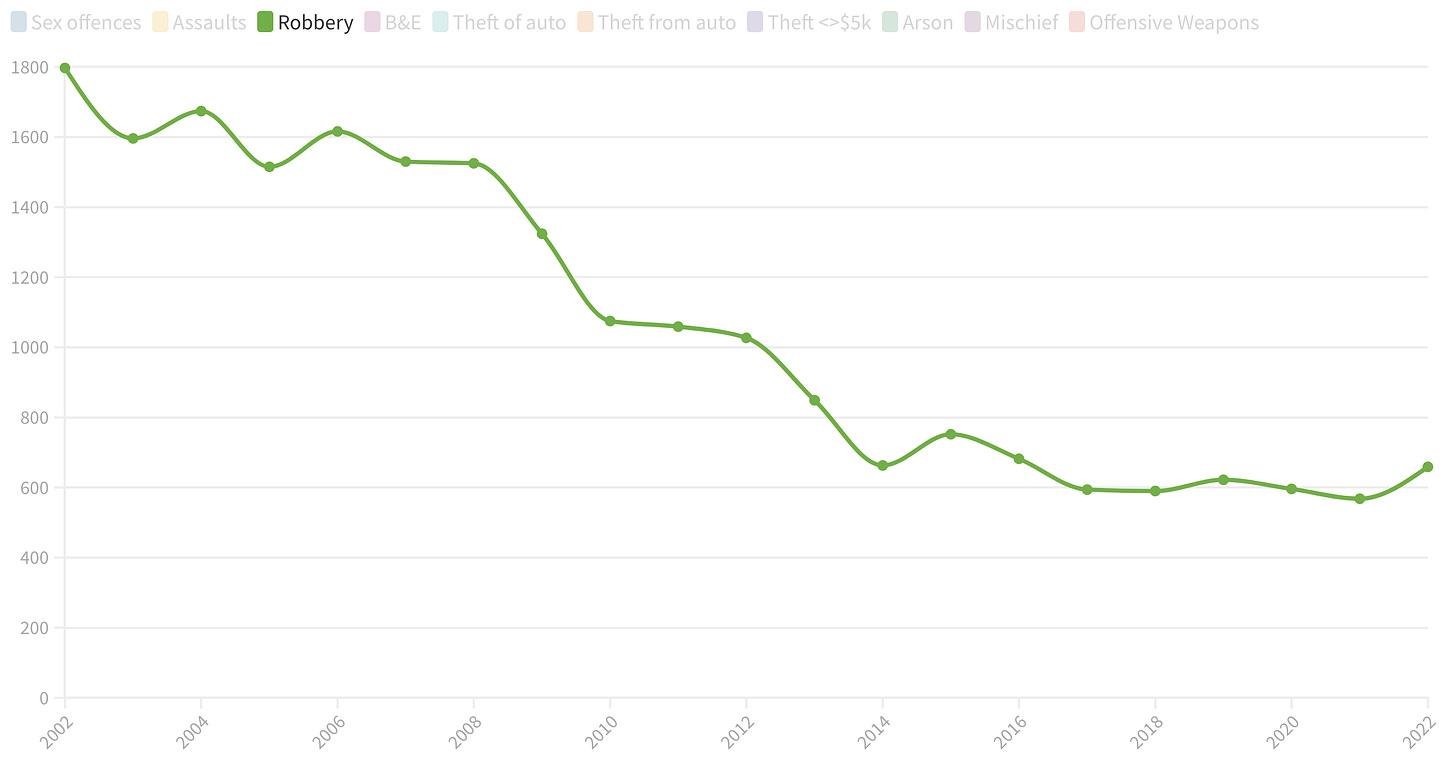

Robberies are up 21%: This is actually the most egregious of the three because you barely even need to pull back to see how misleading this is as some kind of an argument for crime being consistently up in Vancouver. It’s one thing to note that in 2022 there were more assaults than in other years and in recent years, but that isn’t the claim being made in the “crime is out of control” narrative.

As mentioned, these comparisons are drawn between the three-year average of 2017-19 and 2022. No mention is made of 2020 or 2021. And while robberies were, indeed, up when compared to the three-year pre-pandemic average, it was up even more significantly from the year before.

First, I want to note that there’s actually a very notable difference between the first quarter of 2022 and the entire year. While robberies were up 21% from 2017-19 when only looking at Q1, that flattened down to 10.3% for the whole year. The difference was much more pronounced in the year-over-year comparison—robberies were up 17.4% over 2021.

All of that is to say that there isn’t a strong indicator that robberies are consistently on the rise.

In fact, 2021 saw fewer police-reported robberies than any other year since at least 2002, according to VPD stats.

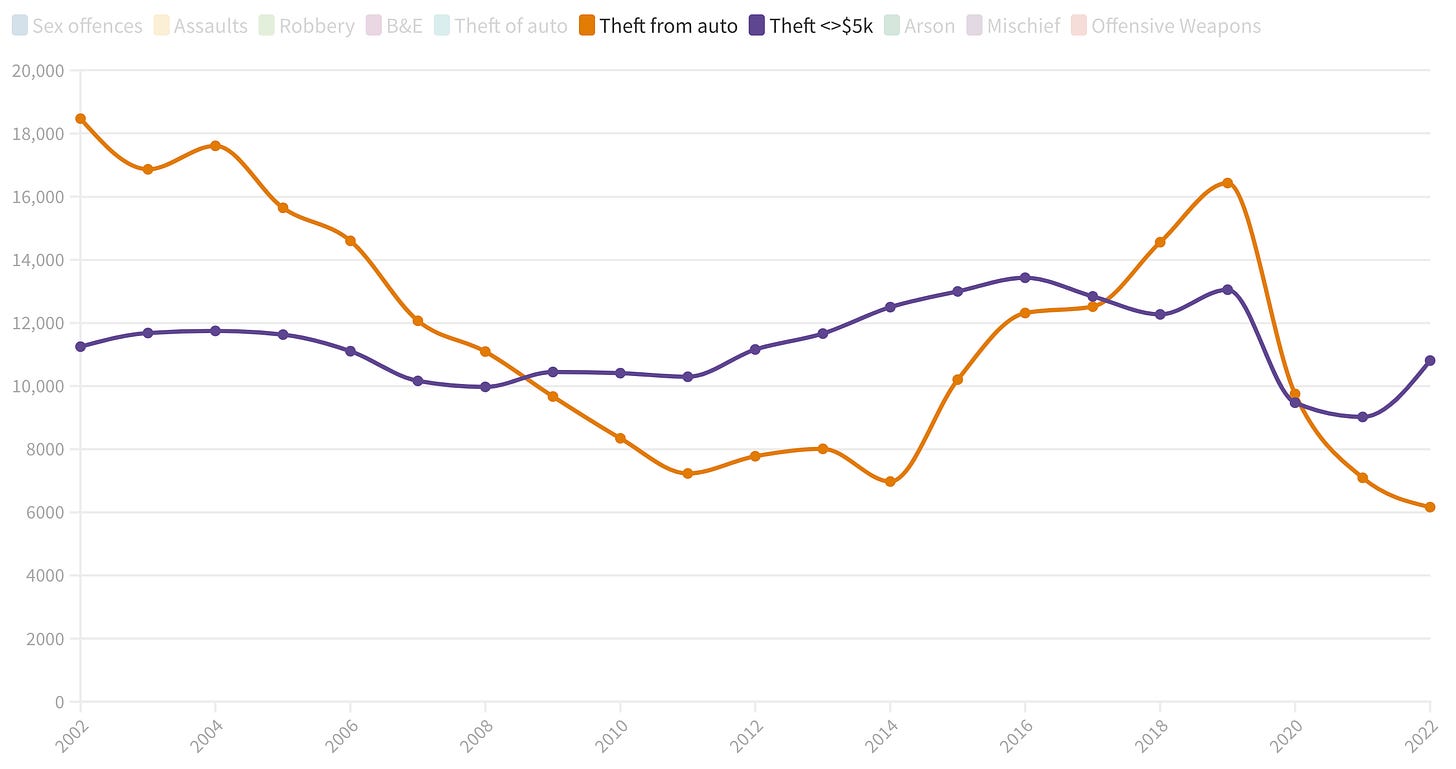

And this is similarly true for a couple of crimes. Break-and-enters? Down at least 50% in 2017-22 when compared with 2002-04 (after 2004, it began dropping fast). Theft of auto? That hasn’t gone over 2,000 since 2009, compared to the 6,500+ in 2002-04 (again, this dropped fast after 2004).

Where crime does trend upwards

That being said, property crime is showing upwards trends over the last five to 10 years. When it comes to theft of personal property, the upward trend is relatively slow, while theft from auto saw a far more pronounced rise from 2014 to 2019. Both have dropped dramatically since 2020, which seems to be pretty clearly related to the pandemic, so it’s tough to use those years in this argument.

The problem with how people talk about out-of-control crime is that they often make it about public safety: people are afraid of their own communities, Gunn tells his viewers. You shouldn’t have to walk down the street looking over your shoulder, retired cop Curtis Robinson says.

It’s intended to trigger an emotional response. They pair anecdotes and highly selective data about horrific crimes with a general collective sense that a select few forms of non-violent crimes are on the rise, and in doing so they fulfill their own narratives: people become afraid of their own communities. They walk down the street looking over their shoulders.

And who should you be afraid of? The Poors. Gunn’s video makes you fear the Downtown Eastside like it’s a haven of violent criminality, but what they fail to mention is that the victims of the said violence are far more frequently the unhoused residents. According to the VPD’s own data, unhoused people are 19 times more likely to be victims of crime.

The narrative scapegoats unhoused people to argue that we just aren’t locking people up enough! It’s the judges, you see! They’re woke activists who are disconnected with the realities of crime, and they’re setting all these violent criminals free!

One of the biggest targets of late is bail: people are just getting out of jail while they await trial, and therefore there are no consequences to reform these hedonists into law-abiding citizens like The Rest Of Us.

The arguments note a couple of maligned Supreme Court of Canada decisions that stated the default should be to not lock people up before they’ve even been convicted of a crime.

This, by the way, makes sense from two standpoints: 1) it’s coherent with our system’s presumption of innocence until proven otherwise; 2) it helps unclog our jail systems, where pre-trial detention made up two-thirds of all those imprisoned in B.C. in 2018/19.

But just as importantly: I’m not sure the rise in property crime has anything to do with bail or with perceived laxity in our judicial system. The rise in police-reported property crimes started well before the 2017 decision on bail that catalyzed changes in how we lock people up on remand.

In fact, it seems to correlate strongly with the affordability crisis in B.C. Property crime began rising in the early- to mid-2010s, and it makes sense. People are, financially speaking, more desperate than they were 10 years ago.

The view of Crime-Doing Hedonists pushed by Aaron Gunn and his ilk has a core function: to make us understand that poverty is not the result of systemic issues but a result of their own moral failing.

Is homelessness a result of the actual housing crisis and the rental market that literally everyone can see is on fire around us? asks Gunn. (Not in so many words.) Marshall Smith, chief of staff to Alberta Premier Danielle Smith, responds: No; 90% of people in the Downtown Eastside are unhoused because of drugs and addiction, not a lack of housing.

Robinson goes even further: “They want to live down there.”

If you’re poor or unhoused, you’ve done it to yourself. And what’s more: you like it this way.