It's time for journalists to stop reporting uncritically on drug busts

Evidence links enforcement to harms, including overdose and death. We need to stop giving cover for it.

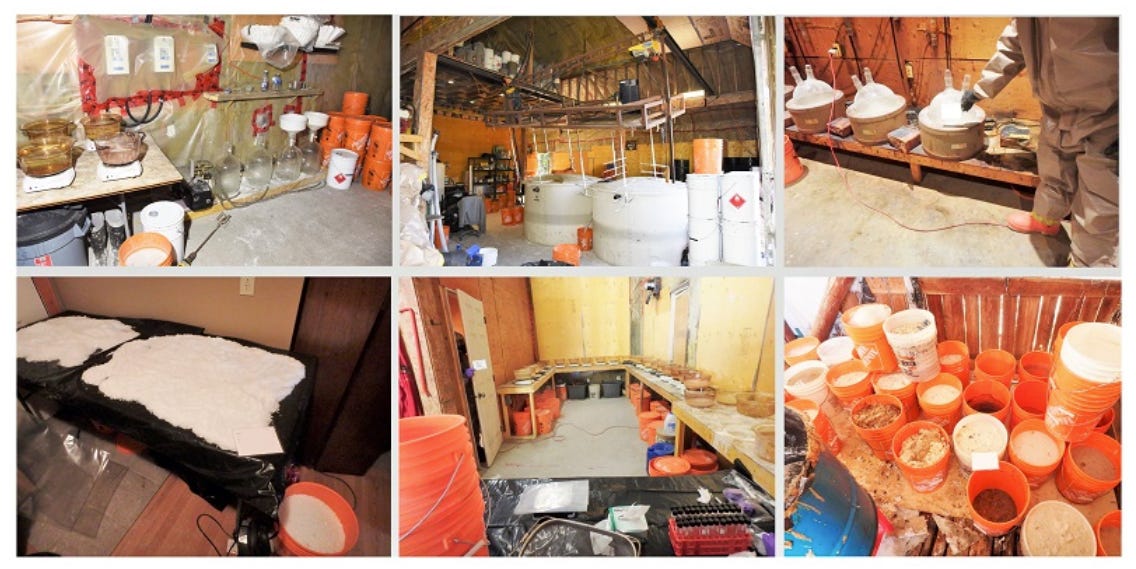

Earlier this month, the BC RCMP put out a news release, saying a major investigation into a drug lab in the small north Okanagan town of Lumby had ended with six convictions and drug seizures worth $258 million.

And it came with a label that was primed for headlines: a “drug super-lab.”

Police claimed it was one of the largest of such labs in the province, and all six suspects involved had been convicted, the most recent convictions coming a month prior to the news release being published.

The police do this from time to time: if convictions from major investigations go unnoticed among the sea of cases flowing through the courts, they’ll put out a news release and pat themselves on the back about it.

And the media will invariably eat them up.

It certainly did in this case. Black Press, Global News, CTV News, Kelowna Now, the Indo-Canadian Voice, the Western Standard, and for some reason the Alaska Highway News (which could have syndicated Castanet’s article from the time of the sentencing) all reported on the news release. In fact, Black Press reported on it twice — once at the time of the sentencing and again when the RCMP published its news release.

Feeding content-hungry media

I’ve been there. I spent much of my career working for content-hungry news outlets that feed off of precious clicks to get their modicum of digital ad revenue, and I’ve participated in the daily news cycle in which police news releases play a major role.

They’re easy content that can fill a website publishing time slot with little effort. In many cases it’s simply too difficult to find another source that might challenge the police narrative. In many more cases, we just trust the word of the police. We’re so trained by crime procedurals and other forms of copaganda that we can’t for the life of us see that police are also humans capable of lying, misleading or even simply making mistakes.

In doing so, journalists act as an extension of police forces’ already-extensive public relations arms. But this is in part where the problem derives: police forces have ever-increasing resources, including in their PR departments, as newsrooms are starved of resources.

In my last staff position, at the Burnaby Beacon, we made a policy of talking about which police news releases we would publish and which we wouldn’t. If it involved drugs, and especially if it was fairly minor, we had more of a discussion about the public good of publishing that press release.

The myth of separating drugs from users

Few people will argue the war on drugs has been a success. And yet, we continue apace, funding militarized police forces that enforce antiquated, harmful drug laws in ways that do harm particularly to marginalized communities. And the media reports on this as if it’s a uniform good.

The first half of the “super-lab” news release from earlier focuses on the facts — names, locations, dates, charges sworn, convictions, sentences, amounts seized, etc. — while the second half of the news release takes another turn. It’s one I’ve mentioned in this newsletter before, and much of the topic of this particular piece builds on or echoes a past newsletter.

In all, the news release spends nearly 500 words writing about the dangers of fentanyl in the drug supply, including statistics around unregulated drug deaths, ending with a quote from Supt. Jillian Wellard, officer in charge of the BC RCMP’s federal serious & organized crime - major projects team:

“With toxic fentanyl being increasingly mixed in with other types of street drugs, the opioid crisis seems to be evolving into a poly-drug crisis. This alarming trend is now affecting far more Canadians, and most regrettably, our children and youth. This is why the dedicated investigators of the BC RCMP Federal Policing directorate, will continue to relentlessly pursue criminal networks responsible for the production, and distribution of toxic drugs into our communities.”

The media, of course, ate this up too, with some news outlets adding quotes from an accompanying press conference, in which officers said the enforcement “prevented many doses of potentially deadly drugs from entering our communities.”

To some of those who understand the drug war has failed, this may still seem like a reasonable statement, if your understanding of its failings is limited to: people still use drugs.

But the problem goes much deeper than that, of course.

The lines between enforcement and harm

It’s actions like this that, collectively, over decades, created the crisis we’re in. The Iron Law of Prohibition, if you aren’t already aware of it, is that enforcement of drug prohibition leads to ever more potent and toxic drugs.

Opium became morphine, then heroin, then fentanyl, now benzo-dope and tranq. In other words, there’s a direct line between police drug busts and the toxic drug crisis we’re currently facing. The result of enforcement is death, plain and simple.

But even then, the short-term results must be positive, right?

Police often claim drug seizures separate people from the toxic drug supply. This is simply bullshit.

As I and others have reported this year, a study out of Indiana finds a more direct and immediate effect of drug busts — specifically opioid busts. Within all combinations of 7, 14 and 21 days, fatal overdoses increased within 100, 250 and 500 metres of opioid seizures.

The reason for this is pretty simple: seizing drugs, whether it’s from individual drug users, from dealers or from producers, doesn’t stop people from using drugs. Surely nobody really believes it does, right? The claim that seizures separate people from the toxic drug supply is willful blindness at best and blatant misinformation at worst.

Instead, people find other ways of accessing drugs. In those cases, they’re less likely to know the dealer, less likely to be familiar with the supply and more likely to die as a result.

This doesn’t mention the violence and disorder and other harms that can result from drug seizures, either.

We in the media are supposed to be critical thinkers. And yet when it comes to drug war propaganda, we fail again and again. Instead of acting as journalists, we become stenographers.

It’s time for that to change. If media is to continue reporting on drug busts, reporters have to begin finding alternative voices to counter police narratives. If we don’t, our credibility on justice and drug policy will continue to falter.

The RCMP officer who just died in Coquitlam centre near my house died executing a drug related search warrant. That latter fact took hours to come out as there was no critical coverage of what the police were reporting. We only learned later the suspect was also shot but expected to survive.

It seems pretty clearly like whatever operation the cops planned was incredibly botched but ultimately it's the drug war that resulted in another death, this time on the side of law enforcement (and the same is true of last year's RCMP death in Burnaby).