'they took everything'

the price of displacement

This post is in partnership with Changing the Conversation, a project on housing insecurity with Douglas College, for which I am serving as journalist-in-residence.

The view from Robson Square was frustrated.

The City of Vancouver’s traffic cameras at Main and Hastings mysteriously went down Wednesday morning, and the media were illegally barred from observing (though some managed to sneak in).

Only a few days prior, the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users uncovered a plan to decamp Hastings. The number of tents had grown to about 80 on the street, according to the city, which also cited safety issues like sexual assaults in the encampment and fire risks involving propane tanks.

If you assume the existence of the encampment is the cause of the issues, removing the camp might seem reasonable—noble, even. But people who live in those tents and those who work or show solidarity with them insist on looking beyond the surface.

I wanted to ask people what they’d lost as part of this displacement campaign.

I wasn’t sure what would be left to see by the time I got there. I’d been in and around court for much of the day, so my view of the situation was limited to social media.

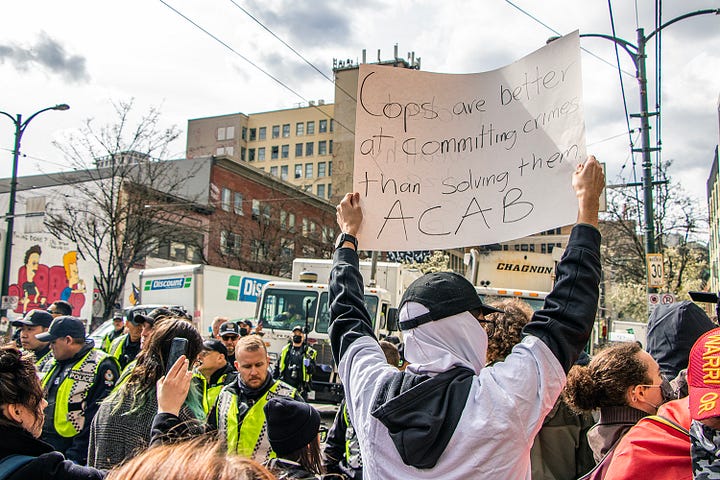

From early rumblings, it sounded like there’d been little resistance beyond denunciation—people were focused on packing what they could into bins. But the day did turn out to be one of confrontation.

I won’t get into the details of the day. If you’re reading this, you’ve likely read other news stories or social media posts already that detailed the day. Plus, I have some thoughts I’d like to put into a future post.

The why

Earlier, I’d posted to twitter: “continually baffled by what they think this accomplishes except for further destabilizing people's lives.”

As the internet is wont to do, I got insults: “Then I guess you’re not terribly bright, are you?” I got the “hell ya do this more!!” type of responses. I got dehumanizing responses: “Taking out the trash.” I got: “I suppose you wouldn’t mind them setting up their tents in front of your home?” And I got replies like this one: “The status quo was no kindness.”

Which brings me to the point of this post: what is the point of the street cleanup? What is the cost and who bears it? And who benefits?

The last tweet I quoted retains the veil of reasonability. It’s true—nobody thinks the status quo is compassionate, least of all those who live in the tents on East Hastings. But it’s still not an argument for anything. Mayor Ken Sim cited the safety issues, such as propane tanks, building access for emergencies and sexual assault.

Each of these is a cost of doing nothing, a genuine safety concern. The obvious response is to do something. The urge to do a forcible street sweep is understandable if you limit yourself to half-thoughts. The moment the justification falls apart is the moment you achieve object permanence—the moment you realize closing your eyes won’t solve the issue either.

The cost

The police couldn’t stay forever. And as they left, a westward procession followed, people moving back to their old spots with what possessions they managed to save. Some had garbage bins labelled “personal possessions.” Others carried tents.

“Pretty much everything,” one person told me when asked what they’d lost. He managed to keep some things in a garbage bin, but he’d lost his tent.

One woman managed to save her tent, but in doing so sacrificed everything else. “They took everything,” she said. She had only the clothes on her back, now. She lost items with sentimental value—things given to her by dead friends or relatives. This echoes past complaints. In 2021, an Indigenous woman told CBC she lost her mother’s ashes in a street sweep. Another person claims the police threw away the cremated remains of a woman’s mother, brother and uncle.

One man told me this week he lost his dog food. His pit bull, MJ is sweet. I ask if I can pet her, and when I’m told yes, I kneel down and offer an open palm. MJ gives it a sniff and accepts some rubs on the head before turning around for the main show: the butt pats, which are accepted with a wagging tail.

I asked if there were services they could turn to for dog food or clothing. But MJ’s owner tells me, “That’s not the point. It’s the principle of the matter.”

Indeed, those losses are a cost of the cleanups. Everything people own is now in the back of a truck waiting to be thrown out. Or perhaps it’s already in a dump.

Also lost is the time it’ll take to get new clothing, new dog food, new tents or other forms of shelter. Proponents of the street sweeps say there is housing and shelter space available. But that doesn’t seem to be true, and the housing that’s available is of questionable quality.

Wade Woodward told the Vancouver Sun and Globe and Mail he wouldn’t accept living at a single-room occupancy hotel anymore. The hotels are notorious for cockroaches, bedbugs and rats. They’re fire traps. One such hotel caught fire last year and burned down, killing two people inside. As Tyee writer Jen St. Denis reported, the fire extinguishers were empty.

So people returned. The woman who managed to keep her tent, with a mischievous grin, moved it into the street for a few minutes after the police wrapped up. It was a statement: we’re still here. Nothing has changed.

The costs of street sweeps are manifold, not only on the part of the people affected—lost clothing, lost shelter/tents, lost dog food, lost sleeping bags, lost sentimental items—but far beyond. Police and city staff overtime. Truck rentals. Disposing of the items taken. There’s the opportunity cost: what work could those involved have done otherwise? The dozens of protesters who showed up in solidarity, the unhoused people living on the street, the city workers, the journalists. And there are the words spilled in news articles and the rage spent by those displaced and those who support them.

The cost also extends to health—the BC Hepatitis Network noted medications can get lost in the sweeps—and quite literally to the risk against life. The Overdose Prevention Society reported drops in attendance, but it’s highly unlikely drug use would have decreased. (We, of course, don’t know if there was any uptick in fatal overdoses in the neighbourhood that day.) And the decampment continued on Saturday, despite a rainfall warning.

The benefit (cost)

And for what? What’s the benefit when nothing changes? People cite the harms in the encampment as if the encampment is the cause of those harms, rather than a symptom of the same issues of poverty. As if decampment will do anything to change it. Women being sexually assaulted in tents isn’t a reason to take those tents away from them. It won’t make anyone safer. It will make it worse.

Another reply to my tweet, using a phrase popularized by Atlantic writer Adam Serwer, echoes loudly in this moment: “The cruelty is the point.” It’s hard to argue against it. What else is the point, if it isn’t to improve anything? If a street cleanup isn’t done with the community, but actively against that community, what else is it but cruel?

The day came to a close and ultimately nothing changed. Well, almost nothing. People are still on the street. People are still unsafe. People are in the same position, only now they have less. Just like, as journalist Justin McElroy noted, in 2014. And in 2015. And 2017. And 2019. And 2020. And 2021. And 2022.

Thursday and Fridays were new days. They were days authorities could have chosen something else. They didn’t.

Who’s spoken out?

Some have raised concerns the current city council has cut funding for non-profits for not “speaking respectfully,” potentially chilling non-profit speech in situations like this. And certainly there are organizations who haven’t added their voice to the chorus of those speaking against the practice. But there has been a resounding outcry from several local service providers and others. Here are just some of them:

BC Hepatitis Network

B.C. Human Rights Tribunal commissioner Kasari Govender

Vancouver Tool Library

Exchange Inner City + Vancouver Urban Core + Coordinated Community Response Network

Kilala Lelum

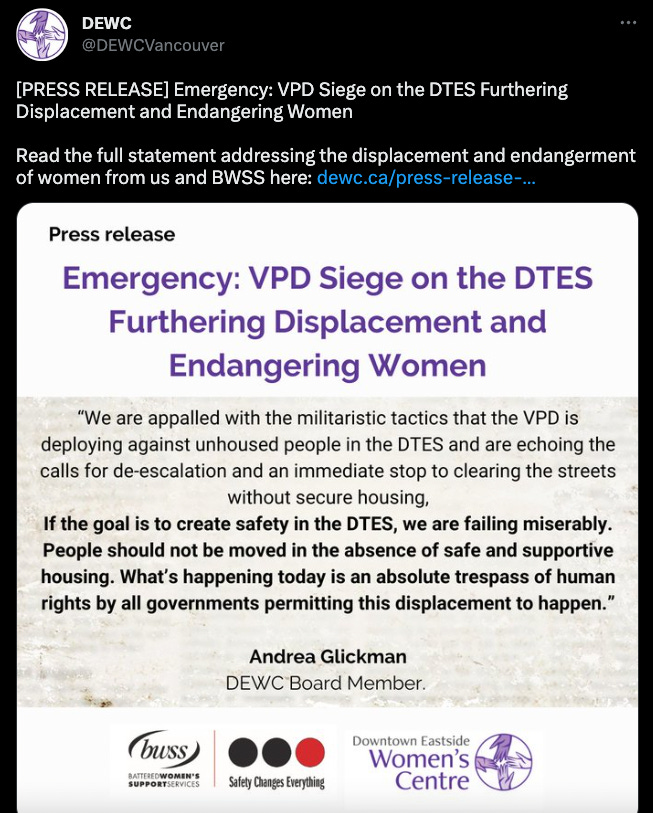

Downtown Eastside Women’s Centre + Battered Women’s Support Services

BC Civil Liberties Association

PACE Society

CUPE BC + CUPE 1004

This last one is contentious, mind you, as CUPE 1004’s own members were the ones doing the decampment. Others fired back, saying CUPE should be supporting workers to resist this kind of work if they truly oppose it.

(With a bonus denunciation from the federal housing advocate.)