There's a vacuum waiting for a party that will take on moral panics — so where is it?

The BC Greens have an opportunity to stand out against the tripartisan moral panic politics. Why haven't they taken advantage?

The BC NDP’s about-face on drug policy, and its turn towards fuelling a moral panic, is a symptom not only of an ascendant right wing but of a lack of political pressure on the left.

While the party doesn’t lack critics from the left — between court challenges and protests, there has been no shortage of pressure from the grassroots — the party sees little threat from those individuals as long as there’s no party that could capture seats in the legislature come fall.

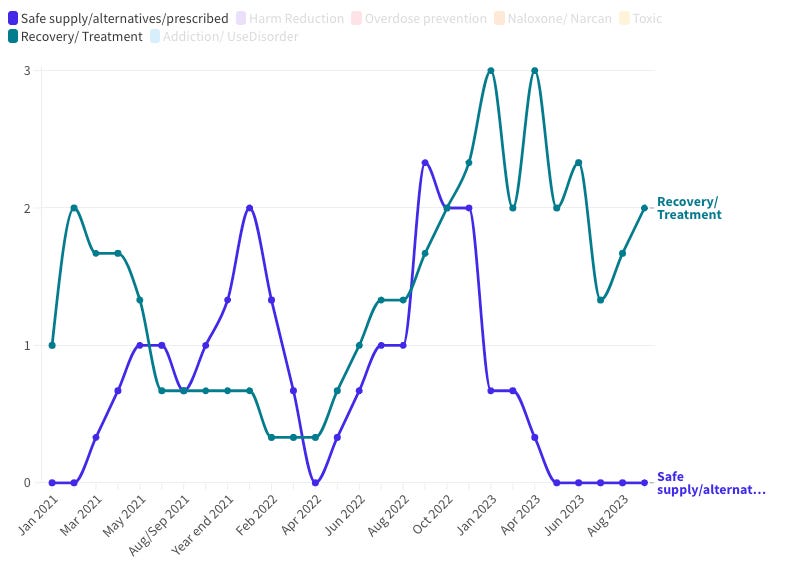

For years, the BC NDP gladly touted the language of harm reduction, even making increasing references to improving access to safe supply in its monthly statements on toxic drug deaths. It did so with the loudest opposition coming from those who said the measures didn’t go far enough.

Political winds turn against harm reduction

The then-most viable conservative party had, as recently as June 2022, given tacit support for decriminalization.

By fall that year, that had begun to change. Vancouver is Dying, a YouTube video by far-right media personality Aaron Gunn, promoted by the billionaire-funded Pacific Prosperity Network, pushed a skewed narrative to blame harm reduction and a supposedly lax legal system for all of our woes.

Soon enough, the lives and rights of drug users became inconvenient, and the BC NDP’s rhetoric shifted notably from safe supply to an emphasis on treatment and recovery.

The inconvenience to the BC NDP is driven by increasing pressure from the right, including an ascendant BC Conservative Party; a desperate, floundering BC United; the right-wing ABC sweeping Vancouver city council; and a federal Conservative Party that is poised to win the next election. But it’s also driven by a convenient (for their purposes) set of economic and social issues.

People across Canada are facing difficult times due to cost of living issues, with a particularly acute issue around housing in BC. Most people feel these economic pressures to some degree, but there are those who feel it more than others — including those who made up the 32% increase in homelessness in Metro Vancouver.

The moral entrepreneurs driving the panic, however, have been successful in diverting at least some of that economic angst onto those same people who are experiencing the worst of it, scapegoating poor drug users for electoral and ideological gains. And rather than countering that narrative, the BC NDP has followed suit.

The party’s turn to the right is reflected in other areas as well, leaning heavily on market solutions in particular to address the housing crisis. (This, perhaps, is bolstered by the party being two-fifths landlords.)

But certainly the party’s greatest shift has been around drug policy, around which a moral panic has seized the province for the last two or so years.

What is a moral panic?

Moral panics are often the cry of a perceived normalcy that is challenged. Its targets include poor, young, racialized, disabled and queer people; immigrants; people from non-dominant religions; and any other deviant “folk devils” that behave or look different from the perceived “normal.”

Moral panics, according to scholars on the issue, draw from a variety of sources: law enforcement, politicians, interest groups, and the media, all self-perpetuating and co-legitimizing. Interest groups advance their interests, politicians are seen to be taking action, police get budget increases to escalate enforcement, and the media sells narratives.

And because each of these is an institution (relatively) independent of the others, they don’t coordinate, but rather affirm one another.

As with any moral panic, the media plays a key role in amplifying and legitimizing exaggerations, mischaracterizations, and blatant falsehoods.

When he coined the term “moral panic,” describing a mass over-reaction to a spate of violence in a small English resort town in 1964, Stanley Cohen noted the particular role of the media in generating the reaction through sensationalism.

Headlines included “Wild Ones Invade Seaside,” “Day of Terror by Scooter Groups,” and “Youngsters Beat Up Town,” according to the 1994 paper Moral Panics: Culture, Politics and Social Construction by sociologists Erich Goode and Nachman Ben-Yehuda.

“The press, especially, had created a horror story practically out of whole cloth. The seriousness of events were exaggerated and distorted-in terms of the number of young people involved, the nature of the violence committed, the amount of damage inflicted, and their impact on the community and the society as a whole,” Goode and Ben-Yehuda wrote.

“Obviously false stories were repeated as true; unconfirmed rumors were taken as fresh evidence of further atrocities. Once the atrocities were believed to have taken place, a process of sensitization was set in motion, whereby extremely minor disturbances became the focus of press and police attention, captured in the headline at the time: ‘Seaside Resorts Prepare for the Hooligans’ Invasion.’”

Driving fear

Ben-Yehuda and Goode outline five factors that define a moral panic: heightened concern about the (perceived) actions of a group; hostility towards a category of people seen as engaging in threatening behaviour; a degree of widespread agreement about these concerns; disproportionality between the threat or perceived threat and the concern or reaction to it; and volatility — the moral panic appears and subsides suddenly and is typically short-lived.

While a moral panic may invent a threat — satanic cults weren’t committing mass child abuse — it isn’t required to do so. What more often defines a moral panic is the displacement of the threat from its true source onto a particular outgroup, or “moral entrepreneurs” apply a disproportionate reaction to that threat.

An early study describing “crack babies” was, in fact, describing prematurely born infants; video games didn’t cause Columbine or other very real mass shootings some have sought to link them to; and Dungeons and Dragons didn’t cause the real suicides the game was said to have caused.

In BC today, moral entrepreneurs claim without substantial evidence that safe supply is causing new “addictions” — despite preliminary data showing “no increase in opioid use disorder (OUD) diagnoses amongst youth, or in any age group,” since ramping up safe supply began in 2020, and despite BC Coroners Service data showing youth deaths from overdose are overwhelmingly from the toxic street supply.

Discrete moral panics

The last factor defining a moral panic, volatility, may seem to discount the sustained moral panic over drug policy in BC and Canada today, but Ben-Yehuda and Goode note that moral panics may extend over longer periods of time as “conceptual groupings of a series of more or less discrete, more or less localized, more or less short-term panics.”

And one could certainly see distinct moral panics over drug use in parks, over drug use in hospitals, over diversion of safer supply, over youth drug use, and over increases in certain types of crime compared to certain other time periods. A recent peer-reviewed paper explored the diversion moral panic in depth, and though the stories differ in content, the “folk devils” and the threatened normalcy over which panic is spread is consistent between them.

Discourse over each of the four above examples has heavily overlapped with one another, both in substance and in chronology, but they draw from separate sources (decriminalization, a supposedly lax criminal justice system, safe supply). Safe supply and decriminalization don’t need each other for a moral panic to form over either one, as much as political actors tend to conflate the two, often using the blatantly false term “legalization.”

Instead, the concurrent moral panics fuel one another and put defenders of harm reduction in the position of fighting not just for one measure that challenges our traditional approach to drug policy but two.

Today’s moral panic

The moral panic we’re witnessing today around drug users resembles more the Seaside Hooligan Invasion scenario than the satanic panic. There are real concerns about public drug use, but they are often exaggerated, and their cause is regularly misplaced.

In parliament, Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre claimed prime minister Justin Trudeau was allowing drug use “on school buses next to children.” Member of parliament Todd Doherty said “extremist drug policies have turned our neighbourhoods into war zones.”

One person who has managed to get an outsized media presence on this file has been Daniel Fontaine, a city councillor in New Westminster, where I live, who when asked on CBC’s The Current for examples of how decriminalization had changed our community, said it “pretty much almost happened overnight,” but could only give one example: a person using drugs in a Tim Hortons — in Maple Ridge.

It may be that there’s been an increase in public drug use in New Westminster, but it was in no way an “overnight” change, and none of this discourse takes into account the increase in homelessness in the region, leaving more people with nowhere else to go.

Conceptions of safety around playgrounds, in particular, have become detached from reality in the public discourse, to the point where, based on media reports, one Edmonton Twitter user was confident in telling me, in Metro Vancouver, that the swings in my neighbourhood are unsafe because of decriminalization.

People have raised concerns about children being pricked by discarded needles, and that does, indeed, happen — and it’s a problem.

It happened at a Victoria McDonald’s, at a Vernon daycare playground, next to a Kelowna family’s apartment building, at a Port Coquitlam park near a daycare, and in a Penticton park.

The trouble is, it happened well before decriminalization. Every example linked to in the previous sentence is from before decriminalization. One of them had nothing to do with drugs and was determined to have been used for medical purposes before being discarded, and another was believed to be unused needles.

That’s not to say that those aren’t issues or to downplay the health concerns to those children at all. The child in Kelowna was hospitalized with a viral infection because the needle was dirty from being in the ground, and that’s horrifying. The point is that decriminalization isn’t the operative factor here — nor is criminalization a deterrent.

Drugs in hospitals

The other issue that has been raised is drug use in hospitals. Media has been nearly entirely credulous of descriptions of bedlam in BC’s hospitals.

Former MP James Moore told Power and Politics he’s afraid for a family member going into Royal Columbian Hospital because there are drug users.

(I spent several nights in that hospital last summer, and it was fine. In fact, the worst thing I noticed there was hearing a young person audibly experiencing discomfort being dismissed by a nurse as they asked for their partner to be in the room with them in the emergency department while they were being assessed for admission. Their drug use was a topic of discussion, and it was clear they weren't being taken seriously because of it.)

And while there may well be issues of drug use in hospitals, a growing list of healthcare professionals have signed on to an open letter describing the discourse as “panic-driven misrepresentations in media about our workplace safety.”

“Let us be clear: drug use in healthcare settings does not justify re-criminalization of possession for personal use,” the open letter states, adding to another letter penned by 11 healthcare workers.

In fact, as I reported in December, there is a benefit to drug users being able to use drugs in hospitals: patients less frequently checking themselves out early, against doctors’ recommendation, because of it.

To the extent there is an issue with drug use in hospitals, the province had a solution: overdose prevention sites. That solution got so far as being announced by health minister Adrian Dix before being quickly turned down by premier David Eby because “every single hospital doesn’t have this issue.”

BC NDP committing to the panic

I mentioned earlier that politicians benefit from moral panic by seeming to take action, but they can also come at it from another angle: convenience. Moral panics often lean on the fact that their targeted folk devils are already marginalized — there’s no heavy lifting needed to drive fear of those individuals.

In the 1990s, the Democratic Party in the US passed draconian drug policies not because they were, to that point, the primary party driving the drug war. Instead, it was easier to cave to it than to fight it, and in some cases, they became some of the loudest voices for the drug war.

We’re seeing the same today in BC.

In the fall, I wrote in the Maple about the BC government’s change in tack on drug policy, and VANDU member Garth Mullins told me the province had “folded like a cheap tent” and was playing into the opposition’s politicking.

In the six months since that article came out, by fighting to recriminalize drug users, the province has only committed further to this.

Where are the BC Greens?

Everyone, including the NDP, can see that what the NDP has done to date hasn’t worked, and the easiest thing to do is fall back on old ways of doing things — that is, incarceration and enforced poverty.

The NDP evidently sees no electoral threat from falling back on those old ways.

Harm reduction advocates haven’t shied away from the media, including holding protests. But the BC NDP may see them as simply disillusioned leftists, ones who they can write off as no-shows in the election, or those who will feel they have no choice but to vote NDP for fear of a BC Conservative government. (That old tactic.)

But for all the media attention that grassroots organizers may get, the only opposition a governing party is concerned about is that which can unseat its politicians.

It would seem an opportunity for the BC Greens to shine — and they have been supportive of a non-prescriber model of safe supply and of decriminalization, even through the moral panic.

But while the BC United and BC Conservatives like Elenore Sturko have been active most days on social media talking about the issue, the BC Greens have been comparatively absent.

As of June 17, BC Greens leader Sonia Furstenau hadn’t tweeted at all since June 13 and hadn’t tweeted on drug policy since May 28. The BC Greens account hadn’t tweeted about drug policy since June 30, and the BC Greens Caucus account hadn’t tweeted on the issue since retweeting Furstenau’s May 28 thread.

In following the moral panic narrative, the BC NDP has come to boost prohibition rhetoric. The party has closed to a sliver any distinction between it and the right-wing parties, all effectively parroting the same lines about treatment and recovery.

The NDP has dropped near any mention of safe supply except when forced to talk about it, opening up a vacuum for any politician to counter the moral panic narratives being pushed from nearly all quarters at this point.

It’s a vacuum the BC Greens would seem perfectly fit to fill, and an issue with which it could distinguish itself as a party not hyperfocused on environmental issues but with a well-rounded set of policies that stand out from the relatively narrow spectrum the other three occupy — so where are they?